In 2015, a Beijing-based UK native, with charisma and a knack for making things happen, founded a project known as Spittoon Collective – cultivating a new multicultural community of creative thinkers. The concept started as a poetry night in a hutong that then expanded to other literary genres, art and music, adding color to a city in constant change.

Fast forward six years and the collective has spread like wildfire from the capital to Dali, from Ethiopia to Arizona. Below, find out what makes this group of passionate individuals unique and how this project is being exported around the world.

A Hutong Start

Matthew Byrne started something he can no longer turn off. The British poet moved to Beijing in 2013 and felt that the capital city’s poetry scene was lacking. His obsession for starting poetry events inevitably led to the founding of the Spittoon Collective in May 2015. “[At the time], the hub of literary activity in Beijing was The Bookworm based in Sanlitun – that was the crystal palace, the beacon of light,” Byrne tells us on a call from the UK to our Guangzhou office.

While Beijing’s bona fide literary institution would go on to close in the fall of 2019, Spittoon would continue to grow as a community for poets and writers, as well as musicians and others in the creative scene.

READ MORE:

Byrne describes the collective as a platform for people to share ideas, from literary works to different forms of art, with projects sprouting from the creative energy within the community.

While studying in Manchester, England, he organized a group called the Unsung Collective with a few friends where they published works from poets outside the university. “At the end of the month, we’d run a drunken, well-attended event, which was kind of the proto-Spittoon, and I didn’t even know it,” Byrne says.

Spittoon originally started as a poetry night at the now-defunct Mado Bar in Dongcheng district’s Baochao Hutong. “In Beijing, you have these wonderful hutong, ancient structures and alleyways that you can walk down and visit cool bars, so I thought it would be good to have a poetry event as it seemed like poetry belonged very naturally to this area,” Byrne tells us.

“The objective now is to discover Chinese voices and broadcast them to the rest of the world”

The readings would mainly be in English, but with an international community a new section called ‘Poetry-in-Translation’ was started, which featured works in Chinese, Afrikaans, French, Arabic, Russian, Spanish, Sinhalese and Mauritian Creole, among other languages.

Poetry and the diverse audience would turn out to be the “well-spring” for Spittoon’s launch into other creative ventures, such as Spittoon Fiction, Spittoon Poetry Slam, Spittoon Storytelling and Spit-Tunes. “We created a kind of theme park-like atmosphere where every Thursday was occupied by a different literary genre or art form.”

One of the collective’s more successful projects to date has been Spit-Tunes, a blend of poetry and music that led to the founding of Poetry x Music, a band featuring writer Anthony Tao and classical guitarist Liane Halton.

Joining organized activities like Spittoon can be a major help for those caught up in a unidimensional life. These groups are especially important in China as people need to build new relationships to find purpose while living in a different country.

In a May 2020 Harvard Business Review article, author Rob Cross notes four life connections that create purpose: spiritual, civic and volunteer, friends and community and family. But among these four connections, the argument can be made that friends and community surpass the others, considering that some folks may not be spiritual, and their families are back home. Having a trusted network and sense of community can make the difference between a purposeful chapter or blip on the radar of life.

As Spittoon gained momentum and more members were involved with various projects, friends and community became the adhesive in which the collective held together.

Beijing-based university teacher Zuo Fei, also known as Sophie, was connected to the collective after meeting some of the members in the spring of 2018. “It was quite an accident,” Zuo recalls over the phone from the capital city. “One of my American colleagues [at the university] told me about a translation workshop, and there I met Matthew and Simon Shieh, who was the original editor-in-chief of Spittoon Literary Magazine.”

Zuo started contributing translations to the magazine and enjoyed working together with new like-minded friends.

Spittoon started putting together a biannual literary magazine the same year the collective started up. The mag was comprised of a collection of the best English poetry and fiction they could find written in Beijing and Chengdu, along with a selection of articles, interviews and translation pieces.

Nowadays, Zuo and Shelly Shan, a poet currently based in Tokyo, are in charge of the magazine, which switched to publishing Chinese writers in translation. “The objective now is to discover Chinese voices and broadcast them to the rest of the world,” says Byrne. The issues, formerly sold at The Bookworm and now available on Weidian, combine a unique array of poetry and fiction with an aesthetically pleasing design.

Spittoon Literary Magazine Issue 7 was launched on April 3

But beyond the pages are the cultural exchanges made between local Chinese and expats volunteering on the project. Zuo describes the process of grouping native English speakers with Chinese speakers for translations in the magazine and the challenge of becoming a bilingual publication. “If we just use one language, then [the magazine] will be much easier [to make]. A bilingual version is way more difficult. I always tell people that the time and energy we put in is no less than that of a big publication or journal, despite having fewer people to make it,” Zuo says.

While she admits to feeling a bit of pressure putting it all together, she notes there is “strong support from other members.”

For the collective, Zuo and other Spittoon members aren’t driven by financial interest but rather a passion to create and share ideas in the literary and arts scene. “I enjoy it very much – it’s voluntary work, but sometimes I tell Matthew it’s like the Spittoon job is getting more important than my regular job,” Zuo jokes.

Byrne has the same mindset, as his job in the UK is separate from his role as founder and director of the collective. “I think that’s the strength of Spittoon. If we occupy the hobby space in peoples’ lives, we can add meaning to their creative endeavors. The skills, experiences and personalities of people are naturally invested in the project.”

There’s plenty of literature on the importance of cultivating a passion outside of the workplace, especially during a pandemic which has caused many to reflect on their lives pre-COVID. Many realize that a paycheck doesn’t necessarily equal passion, and often our jobs don’t quite enable us to be inventive or experiment the way we want. That’s where a new side hustle or creative project comes into play.

One of the main benefits we’ve learned regarding Spittoon is the opportunity it gives members to create and contribute something new and involve others in the community. Byrne provides us with an example of the person running the collective’s Instagram account, simply going beyond the pale after starting to attend their events in Beijing.

While his parents might be confused by his “obsession” with a project that doesn’t benefit him financially, Byrne argues, “If so many people are interested in something that you created or managed, then it’s difficult to let it go. You feel like it’s somewhere that you’ve actually had an impact.”

China Calling

It wasn’t long after Spittoon got started in Beijing that it found another home in spicy Sichuan province. Annie Leonard, the Spittoon Chengdu leader, discovered a love for the PRC dating back to 2005 when her family moved from Detroit to Shanghai for a job with General Motors.

“The China bug bit me early… I thought China was really cool and wanted to live here forever,” Leonard recalls over a phone call on her way to her Sichuanese husband’s cafe.

The Harry Potter-themed shop, aptly named Harry’s Wizard Cafe, is one of the locations where Spittoon members will get together in Chengdu for various literary events. “We’d like to make it into more of a cultural hub, kind of like what The Bookworm [Chengdu] used to be,” says Leonard, who originally joined The Bookworm Writing Group before starting up the collective in the provincial capital.

Harry’s Wizard Cafe in Chengdu

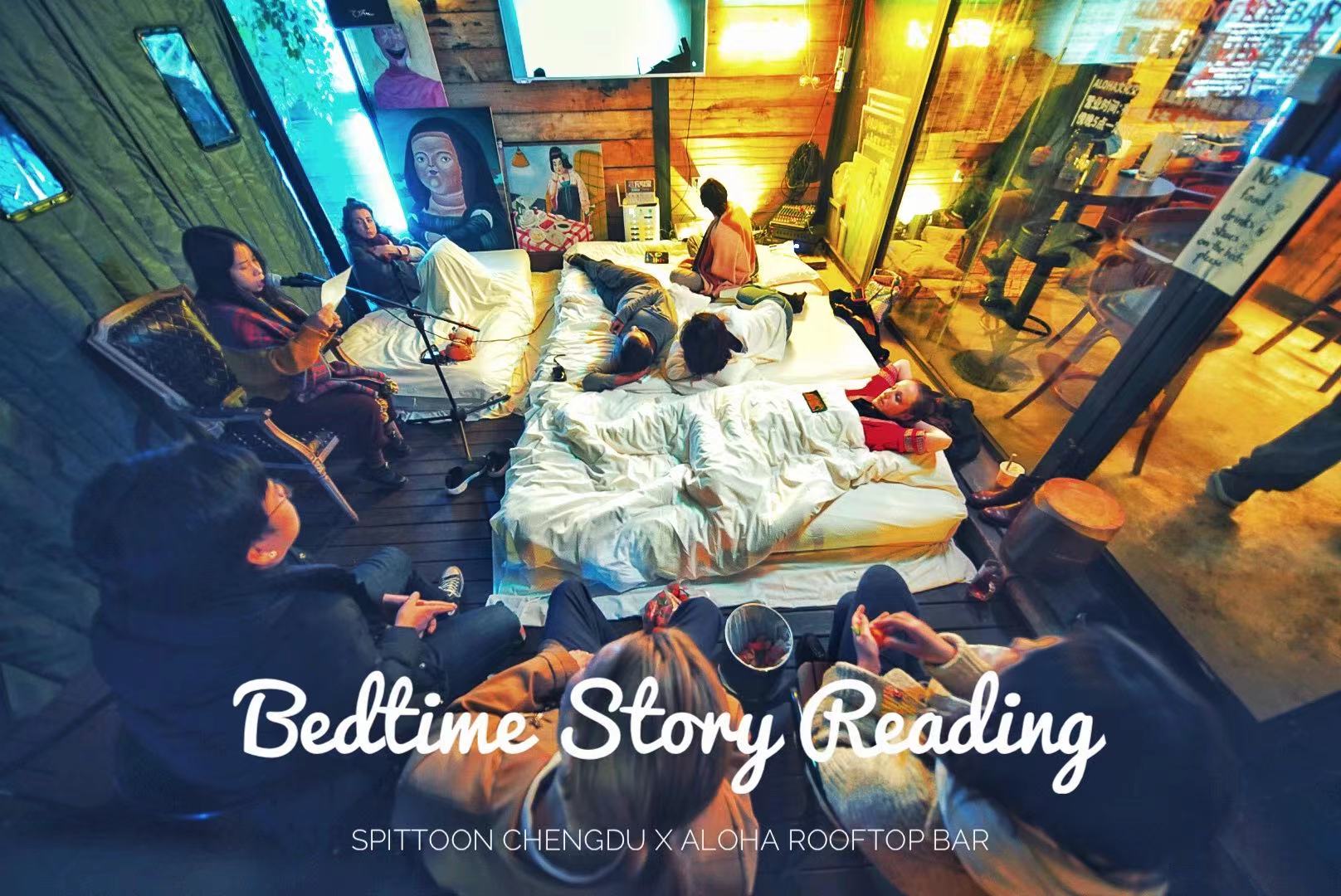

She learned about Spittoon in 2017 after another group, the Loreli collective, interviewed her about Chengdu’s writing community. From there, Leonard would go on to connect with Byrne and other members and start a new chapter for the arts collective. Spittoon Chengdu has since hosted monthly and bi-monthly events for poetry, prose, slams, competitions and music poetry – similar events to Beijing.

“The China bug bit me early... I thought China was really cool and wanted to live here forever”

But Leonard points to one stark difference out in western China. “We are slightly different from Beijing as in we are more of a mix of locals and foreigners. Beijing was originally more expat-focused, but just by nature of Chengdu, there is a lot more integration of Chinese and a lot of foreigners here also speak good Chinese.”

One of the events Leonard hosts bilingually is a multilingual night, which celebrates a lot more Chinese writing among other languages.

Chengdu is what Byrne describes as one of Spittoon’s two established cities, while other collectives are forming in Shanghai, Xi’an, Shenzhen as well as Dali – the first Chinese-led Spittoon collective.

From what we gather through Byrne and Leonard, it’s the transient nature of expats in China that’s led to new collectives forming in other urban areas – along with a passion for literary creation.

It does have its drawbacks, of course, as Zuo expresses that many of the friends made in Beijing sooner or later move on to the next chapter of their lives. “Every time someone has to leave, it’s difficult. Many of my girlfriends are American, and they recently left – making every moment they’re here something special,” says Zuo.

On the other hand, there’s a growing interest in poetry and other art forms among China’s youth that keeps Spittoon expanding its audience in the Middle Kingdom. Zuo tells us about multiple aspects that encourage Chinese locals to participate, from having an opportunity to practice English speaking and writing in an international setting to learning more about themselves.

“Because the changes over the past 20 to 40 years [in China] have been so rapid, these days we realize it’s time to take another look at ourselves, or in a cultural way to rethink the Chinese identity and traditional values in terms of poetry and literature,” she says, adding that many people in the ’80s who went to study and work abroad, especially in Western countries, are ready to return home. Zuo notes that China’s younger generations are also showing an interest in foreign poetry.

She runs a WeChat platform called 外国诗歌精选 (Waiguo Shige Jingxuan), which introduces foreign poets and their translated works to Chinese readers. But beyond shared interests, Zuo describes her own reason for joining Spittoon as an opportunity to bridge the gap of language and cultural barriers between China and the West.

Going Global

Spittoon isn’t slowing down anytime soon. The success shared among Chinese cities has transcended the collective to the world at large. Byrne’s excitement was apparent over the phone as he told us about up-and-coming collectives in Africa, Europe and the US – a sign of the potential for a group that started out in a hutong bar.

“People find out about the community and join and then leave after their work contract ends, taking the seed of Spittoon elsewhere,” says Leonard, noting that Spittoon collectives in Riga, Latvia, and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, were started by two women who previously members of the Chengdu collective.

In Beijing, some of the early members have since left the capital and carried the project onto new destinations like Lisbon, Portugal, and Gothenburg, Sweden.

After getting mixed up with Spittoon three years ago, David Huntington has brought the group’s creative energy to Tucson, Arizona, where he returned to school in August 2020. He volunteers as the managing web editor and has helped organize and host events in Beijing and Shanghai. Eventually, Huntington “missed it enough” when he got back, so he brought the brand to the US. “I felt like I hadn’t noticed anything similar to [Spittoon] like an open mic night or poetry reading night, so I tried to start one, and it’s worked out so far,” he tells us over a WeChat call. Still in its early stage, Spittoon Tucson has done three meet-ups virtually as a result of the pandemic.

“People find out about the community and join and then leave after their work contract ends, taking the seed of Spittoon elsewhere”

Huntington brings up a unique challenge that the collective doesn’t encounter as much in China. “In the US and other places, it can be a bit intimidating to do literary events because it feels like it needs to be of a certain quality and approved by certain ‘gatekeepers’ and things like that,” he says. However, he points out that Spittoon has demonstrated that there’s a demand for participating in literary activities and that communities can be built without anyone having to approve it. “Without Spittoon, I wouldn’t have had the gumption to come in and start an event.”

As Spittoon continues to spread and empower individuals interested in language and culture, Byrne tells us that he’s positioning himself more in the international center to try his luck at growing the collective more outside of the PRC. While still involved with the group’s China operations, he says his “China timer was going off,” which prompted a move back to the UK.

There are notable challenges for Spittoon, from funding projects such as the literary magazine to the mercurial nature of the collective’s members. Byrne describes the hustle to gather resources at times, saying previous projects were funded through magazine sales, ticketed events and fundraising campaigns.

But some of Spittoon’s challenges are also unique opportunities to share this all-encompassing literary and arts brand and its Chinese roots with the rest of the world. “The diversity in our output is really cool and sets us apart,” he says, hinting at the possibilities of connecting Spittoon collectives overseas with the more established Chinese cities.

He views China and Beijing, in particular, as the blueprint on how to grow the community into a global arts cluster. “If I create a [group] in the UK similar to Sweden, then that can be a conduit to draw out more content from China into the UK that’s generated from within China,” he says, suggesting potential projects like linking university students with Chinese poets to create dialogue through postcard poetry.

His ideas racing over the phone, Byrne’s passion for Spittoon is contagious, and we hope to see it thrive for years to come.

This is a place for show life about china, If these articles help you life better in china, Welcome to share this website to your friends, Or you can post questions about china life in FAQ, We will help you to find the right answer.

Recent Comments